The Movie-to-Musical Menagerie Part 3: From Silver Screen to Great White Way

- Ember Sappington

- Apr 9, 2022

- 6 min read

Written by: Ember Sappington, Staff Writer

This is a running series that is published monthly. To read the previous installment of the series, click here.

So, from that early opening of the first movie-to-musical adaptation, The Spring Chicken, I didn’t find anything similar until the 1950s. Even then, it wasn’t all that similar. Film technology had advanced so much from where it had been in the 1890s. There was sound, the visual quality was much clearer, and so much more. And from this point of progress, and also the huge increase in the canon of film available for a stage adaptation, I found the movie-to-musical adaptations we are bombarded with today starting to take shape.

In the 1950s, this trend really started to take off. There were only three seasons that went without an adaptation of this sort opening on Broadway. Usually these movies were from the two decades preceding the opening of their Broadway counterpart.

To start understanding how the new generation of movie-to-musical adaptations were being received, I turned to the run-lengths and reviews of the stage shows. The average run of a musical in the 1950s was about 600 performances. Our dear (or dreaded) special brand shows did not come anywhere near close to that average.

The most successful was Fanny from the 1954-55 season. It ran for 888 performances, which was above average, a standout in my lineup of maladapted misfits. It was adapted from a 1932 French film of the same name that was critically acclaimed. Most of the films that were adapted to musicals during this decade were similar, often foreign films with successful releases or massive American hits, frequently with critical acclaim.

Pictured above: Fanny the musical (top left), 42nd Street the musical (top center), Seventeen the film (top right), Carnival in Flanders the musical (middle left), Seventeen the musical (middle right), 42nd Street the musical (bottom left), 42nd Street the musical (bottom center), and The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond the film (bottom right).

The exception to this that I found from the 50s was the adaptation of the 1940 film Seventeen, which was reviewed as “a barely tolerable little comedy, paradoxically imitative of its imitators” at its original film release. It seems to have remained such for its day on Broadway, having about the average run for one of these adaptations during this time, that of 182 performances. The show from this decade's batch of adaptations that performed the worst, with only 6 performances before closing, was Carnival in Flanders, an adaptation of the highly acclaimed 1934 French comedy, La Kermesse Héroïque. It was reviewed as “laborious and banal. As usual, the theatre has lavished a lot of wealth and talent on this hokum”. So, all in all, not a great start, from what we see here. But, it was still where these transfers from screenplay to stage show started to gain traction.

This is the decade that set many of the patterns of how movie-to-musical adaptations would be produced in the following years. As the average run of musicals on Broadway would increase, the run of these movie-turned-musicals would stay far below that mark, with the exception of one or two shows per decade. Since the 1950s, there has not been a decade with more than three seasons without an adaptation of this sort hitting the great white way. The movies selected for live musical adaptation continued to be chosen from well performing films from the previous two decades. It worked well enough, half of the time. It took a lot less effort and a lot less time than creating an original musical from scratch. Time and effort are money. But, this got me thinking, there had to be a way that would be much more profitable than using average-to-hit movies, often foreign, and adding a musical component. Weren’t there better properties to use for this?

Apparently, Metro-Golwyn-Mayer (MGM), the famed Golden Age Hollywood studio, was thinking the same thing. The studio was in an immense amount of debt, had failed to put out a successful hit in years, and was in threat of bankruptcy. So, the studio turned to Broadway. MGM owned the rights to some of the most culturally significant films and most successful musical films of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s (Think The Wizard of Oz, Singin’ in the Rain, An American in Paris!). In an attempt to save the studio, the old hits’ screenplays were pulled from storage and brushed up and sent to Broadway to see if they could rake in crowds as they had in the past. It worked, and it worked well.

Out of the twelve movie-to musical adaptations that opened on Broadway in the 1980s, five were old MGM musical classics. While these musicals performed under the average run length, they were profitable. The best performing shows from MGM during this decade were Woman of the Year and 42nd Street. Warner Brothers, in a similar state of financial distress, would follow suit. Warner Bros. would send 42nd Street and The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, the former would run for 3486 performances.

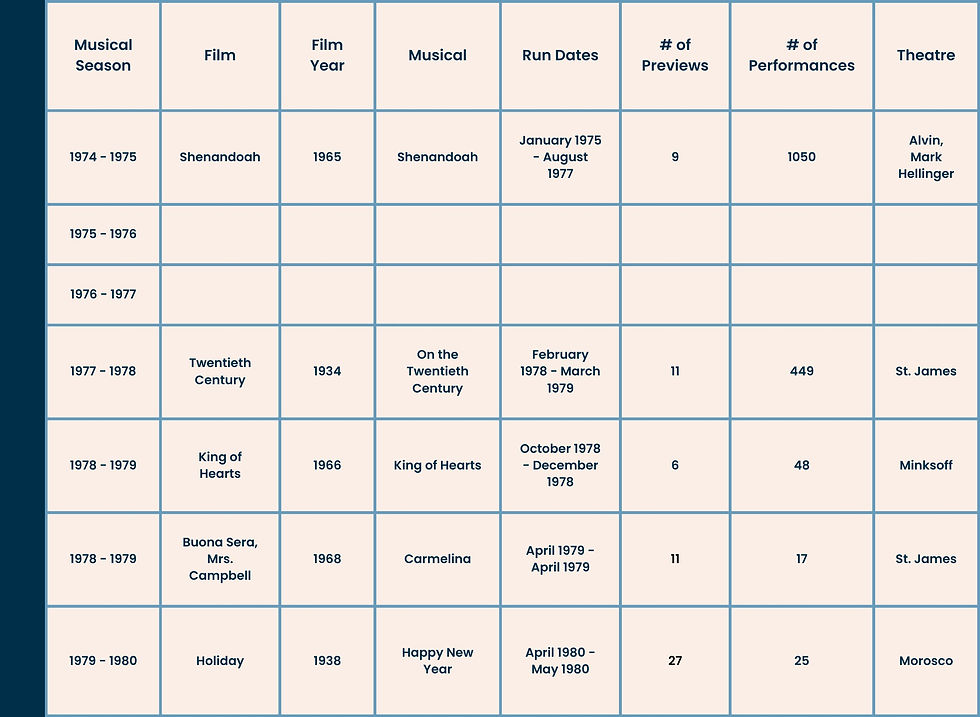

Pictured above: Spreadsheet showing all movie-to-musical data from 1960 - 1980.

The thing about MGM churning out these screenplays-turned-stage-shows is there’s so many of them. They take so little creative effort because all of the creative decisions were made decades ago and were well received by the public. Where an original would call for new music to be composed, an adaptation has songs that are part of the Great American Songbook. Because all of the intensive creative work has already been done, all of the artists that could have been employed to do it are not needed. They are cut out of the creative process, and are denied another job opening. The work of people long gone, although respected, takes the place of this generation’s great writers, designers, composers, and lyricists. Something about that doesn’t sit right with me.

On the other hand, there’s something about the situation that led to the creation of these shows that gives me pause. MGM, however monstrous and notorious its history with creatives was, is one of not the most influential and groundbreaking movie studios of the early cinematic days. The storylines, techniques, stylistic choices, and famous artists that came from MGM have shaped the way that films are made. That company, despite all of its successes, was in peril. If there's anything I’ve learned from the past two year, it's been what it feels like to be in peril.

I’m currently in pre-production for TTS’s production of a devised Henry IV, directed by the genius Chris Anthony. She said something recently while working on this process that has been in the back of my mind while looking at these MGM and Warner Brothers movies from the 80s. While talking about how resistant some theatre people are to interacting with Shakespeare, she brought up how Shakespeare has been used as a tool of gatekeeping, how it is often wielded as a weapon that causes people’s capacity to love Shakespeare to die a death of 1,000 cuts. That part of the place that Shakespeare holds in our culture can’t be denied or go without acknowledgment.

Think about our current circumstances. Nobody in theatre has money right now. Chris pointed out, when funding is low, Shakespeare is one of the safest financial decisions a theater can commit to. She lined up some great points, it’s in the public domain, so no royalties, no licensing issues. That also means you can do whatever you want to the text. Like it or not, there’s going to be a lot of Shakespeare in the next five years. When you think about that, it makes it a little bit harder to castigate a company that’s just trying to bail itself out, no matter how unoriginal the product it puts out is. When I started the research for this project, almost two years ago now, I would have been quick to condemn these companies for putting out cash-grab shows because they come with a built in fanbase, but after two years of seeing the theatre industry suffering, things become a little more grey. The lines between uninspired and just trying to keep your head above water become blurred.

When I looked at these shows, I thought to myself, ‘yeah, that makes sense’. These musicals were written in the style of a classic Broadway musical. They were taking inspiration from the stage form of musicals, and so the transfer to Broadway is reasonable. They don’t really vary from the shows opening on Broadway when they were opening in cinemas, except for the fact that they were filmed. Some of them feel like they could have been adapted from the stage for the screen. Putting them back onstage just seems sort of—natural. While it is simple, and sort of uninspired, it just seems like they fit up there onstage. Maybe it's that all of the production and effort needed for these musicals was put in way back in the thirties and forties, that at one point there was a lot of creative energy put into them, and they were cohesive solid works that make sense as a whole, that went to quality checks. I’m not sure, but it really might be coming from the fact that you could have told me the movie 42nd Street was adapted from a stage musical, and I wouldn’t think twice. But, maybe that’s just me.

These two companies would continue to put successful film properties on Broadway stages through to the present day. Warner Bros. is one of the production companies responsible for most of the 114 movie-to-musical adaptations. A surprising number of these shows have been produced by the same small circle of only 20 different producers and companies. We will take a look into this aspect of this phenomena in the next installment.

Love what you're reading? Subscribe to our newsletter!

Comments